|

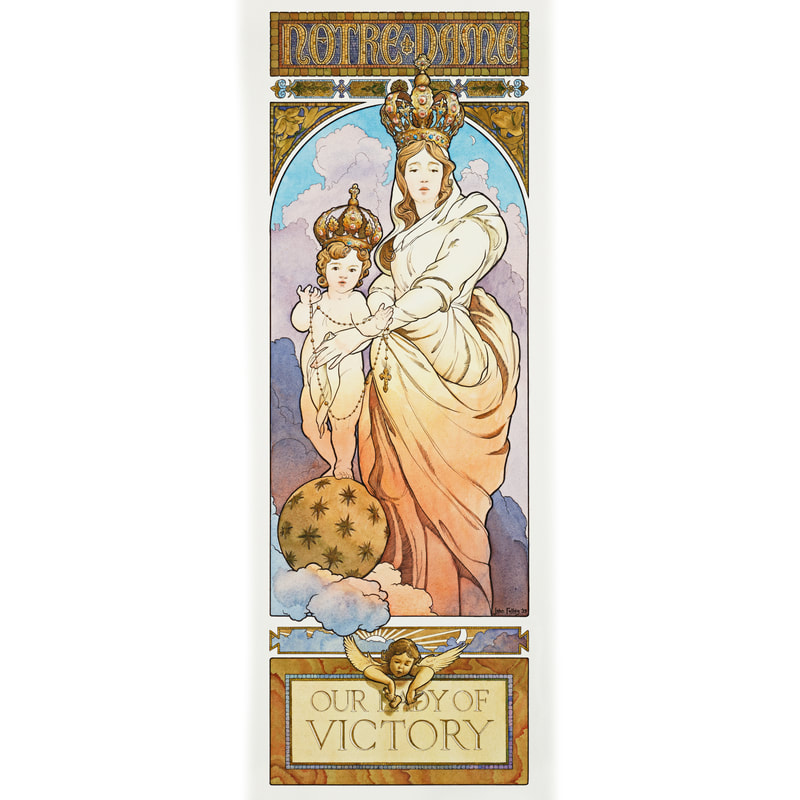

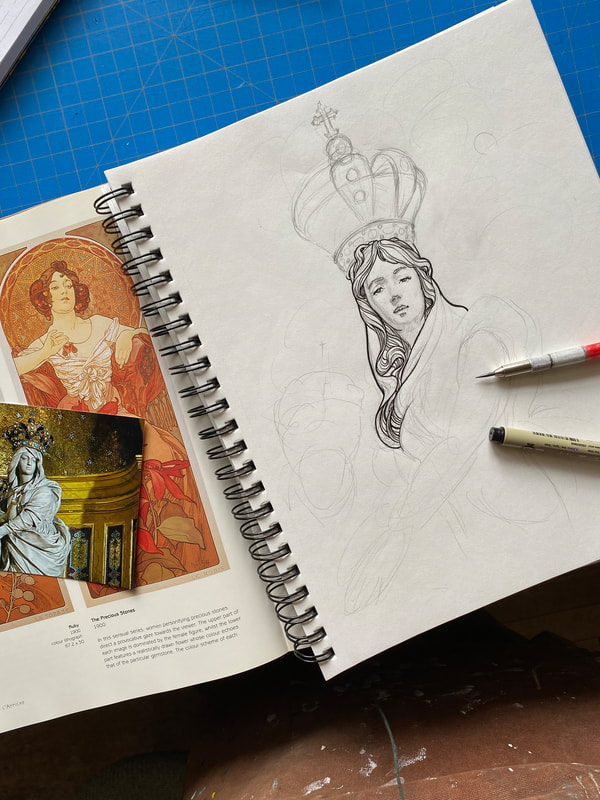

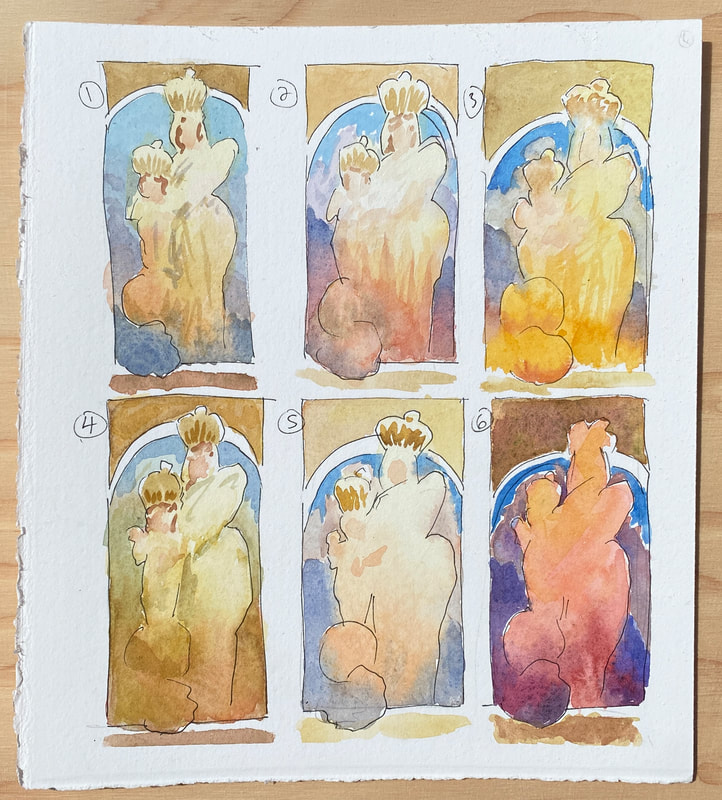

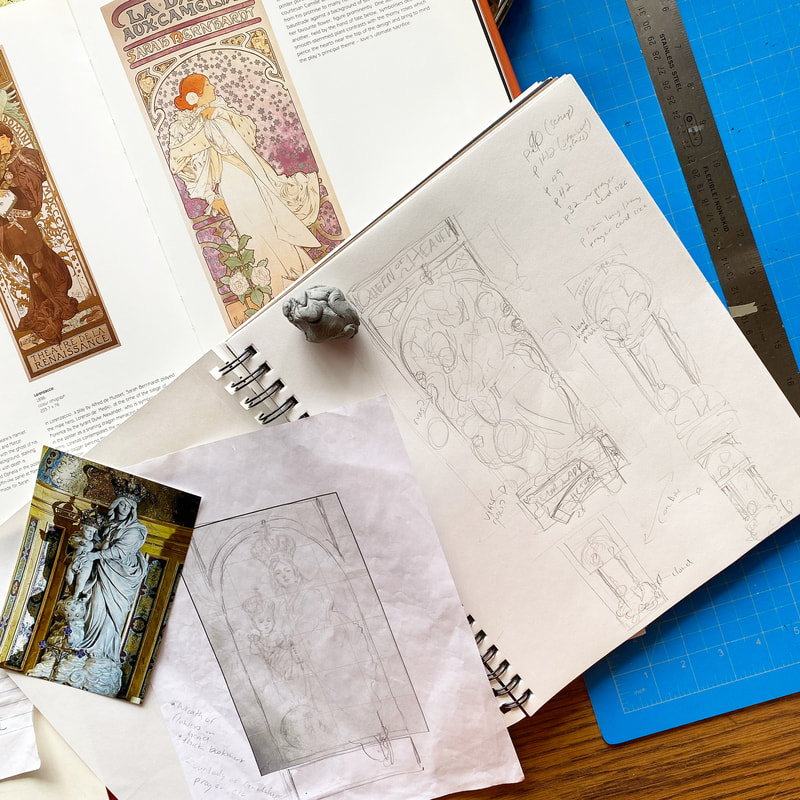

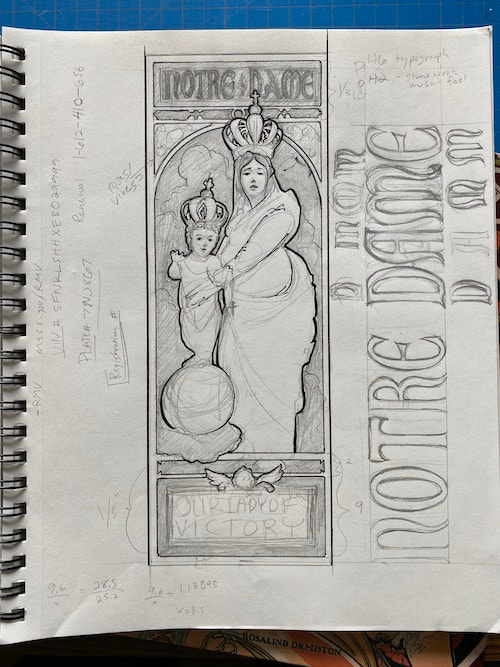

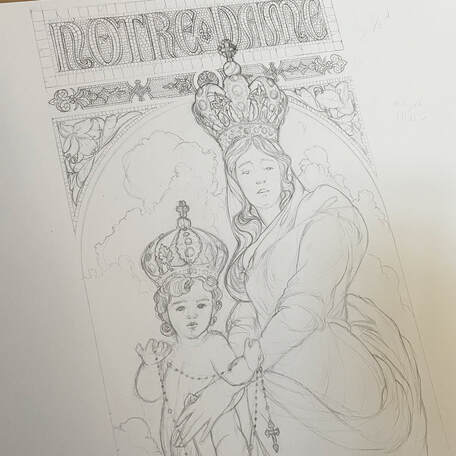

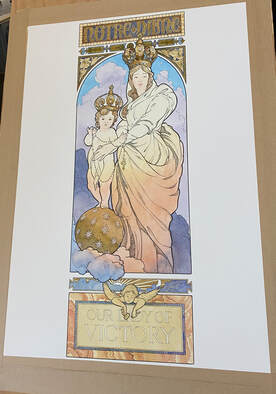

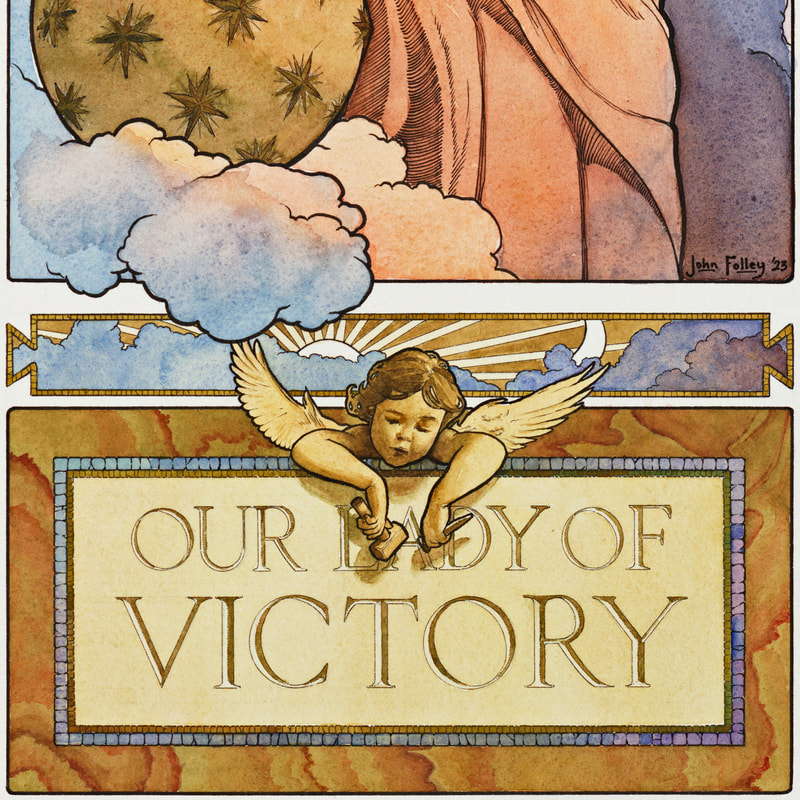

Sometimes, an artist produces commissioned works, working with a patron's vision. Sometimes, an artist produces independently, working out his own vision. And sometimes, it seems, something happens that's a beautiful "in between." This new work is one of those pieces. Our Lady of Victory, 25"x9" Ink and Watercolor on paper Let me explain: a version of Our Lady of Victory wrought in a style inspired by the work of Alphonse Mucha. On the one hand, this was a bit of a segue from my main studio work which, as you know, is oil painting in the Boston School tradition. On the other hand, it's a strain of my work that has been growing recently, from my recent Children's books A Child's Christmas ABC Book and A Child's Christmas Counting Book, which were also inspired by Mucha, and just a general pull in the direction of the Beaux Arts master. If you've been watching my Instagram updates and following along with my newsletter, you've noticed this study of mine. A Parisian encounterEleven years ago this month, I rented a tiny apartment in Paris for my honeymoon with Deirdre. It was barely large enough to fit me standing up straight; we affectionately called the spot our 'Hobbit Hole in the Sky.' When we arrived there in the 2nd arrondissement, we found that we were perched just over the little church of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires (Our Lady of Victory). Over the next few weeks of strolling the city streets, visiting museums, painting and drawing together and munching baguettes, arriving back at Notre-Dame-des-Victoires became familiar, and the church was our home base in a foreign place. Like all the churches in Paris, Notre-Dame-des-Victoires is architecturally stunning, imbued with a historic sense of holiness, and packed with painted masterpieces. Perhaps most strikingly, there is, in a side chapel, a large statue of Our Lady of Victory which is surrounded by artistically arranged piles of crutches that were left there by crippled pilgrims -- pilgrims who prayed for Our Lady's intercession and walked away healed, leaving their walking aids behind. It was before this same statue that St. Thérèse, whose sainted parents were devoted to Our Lady of Victory, once famously prayed for discernment about her vocation. We attended daily Mass there several times and became on friendly terms with the priest who was pastor there. At the end of our visit, this kind priest presented us with a small replica of the famous statue of the Victorious Virgin as a gift to take home with us. We were deeply touched by the gesture. We felt a special connection to this little corner of the City of Lights and a new patroness for our future family: Our Lady of Victory. The statue has always held a place of honor in our home. A new take on the MadonnaTwo years ago, I was commissioned by a patron in the Midwest to produce an oil painting of Our Lady of the Rosary (the same iconic image as Our Lady of Victory, under a slightly different title and understanding). It was an occasion to bring my little statue into the studio for study and inspiration. That painting was settled in Indiana some time ago, but the image of Our Lady of Victory/Our Lady of the Rosary has been on my mind and heart... An ink and watercolor, "Art Deco" version needed to be born onto paper. This seemed perhaps to be a bit of a 'pet project,' a pure labor of love... something for me to go ahead and try. But it seems that the goodness of this idea is not just inside my head. As I was sharing the work in progress through Instagram, another patron reached out to inquire about it and ended up purchasing the painting when it was about halfway done. As you can imagine, this was truly a thrill for me! To have my 'concept' adopted at that stage was very affirming and exciting. Since then, not only have I received many more inquiries and positive feedback from many of you about this painting, but I have also had inquiries about further commissions along these lines. So, clearly, my experimental marriage of sacred art with Mucha-style technique has much territory yet to be explored -- and I can't wait to go there. If this is something that you're interested in being a part of, please be in touch to discuss a commission; I would love to have a conversation with you! About the piece itselfYou will notice the symbolism of celestial bodies in the image. Mary is Queen of Heaven and has often been likened to the Moon -- she is not the source of life herself but the perfect mirror of grace, just as the moon reflects the Sun. Here she is imagined as a Lady strong but serene, powerful through her Son but humble in herself. Her mouth is resolute but quiet; the infant Jesus is more poised to speak to us and He offers us the Rosary, that powerful prayer. All the colors of dusk and dawn are around the two figures, but they stand forth in pure light, triumphant. In the corners are stylized lilies which represent Mary's purity. And the various stone touches hearken back to the architecture of Paris. I wanted the crowns especially to stand out with extreme dimensionality and splendor. (Bonus detail: You may notice a similarity between the face of Jesus and the face of the angel who has just carved Our Lady's title into everlasting stone... both are modeled after my little daughter Symphorosa.) I have heard from many of you that Our Lady of Victory is a title that seems very relevant at this historical and cultural moment. Perhaps you are sensing, like me, the spiritual battle taking place around us; perhaps you're occasionally feeling beleaguered and looking to Our Lady as the fair champion we need. We know the gates of Hell will not prevail against Christ's Church. Even when we feel besieged, Mary is a heroine of this story and shares her power through the Holy Rosary. Prints!While my original Our Lady of Victory is awaiting framing in its new home in Texas, I am making prints available for all of you because of the way this image seems to have resonated with so many.

I have worked closely with an excellent giclée print maker here in Massachusetts and am very excited to have him reproducing my work on beautiful, archival, creamy paper with slight texture that is reminiscent of the original watercolor paper. I vetted a few test options and am confident that the quality and color of these prints will be a beautiful and excellent representation of the original work! I'm trying out a print order form for your ease and my organization. Please click through to place your order!

1 Comment

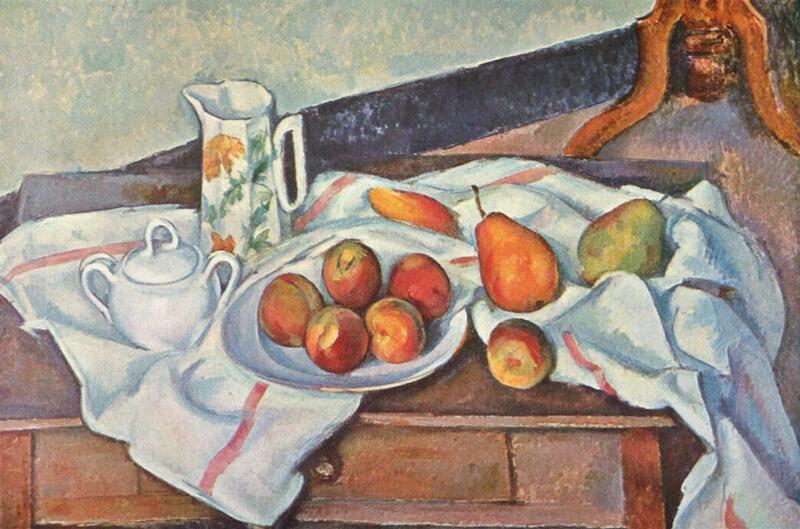

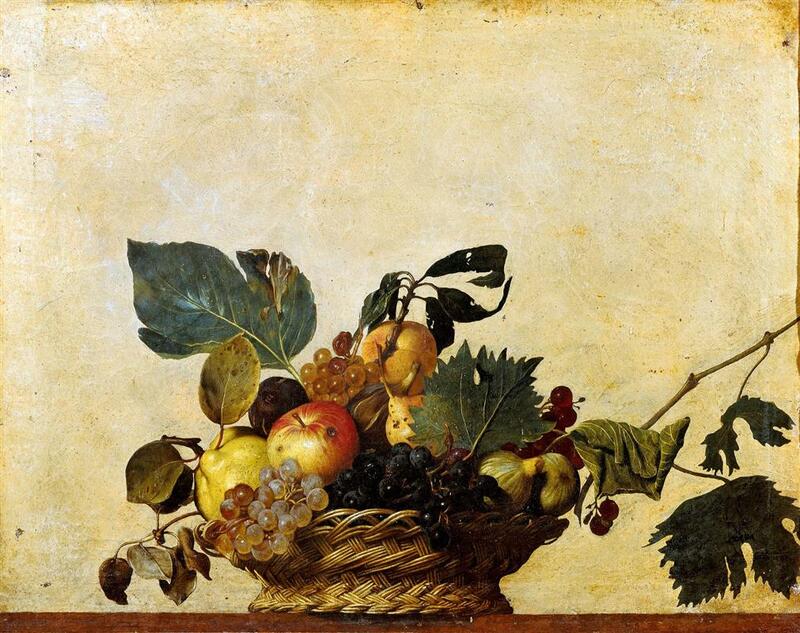

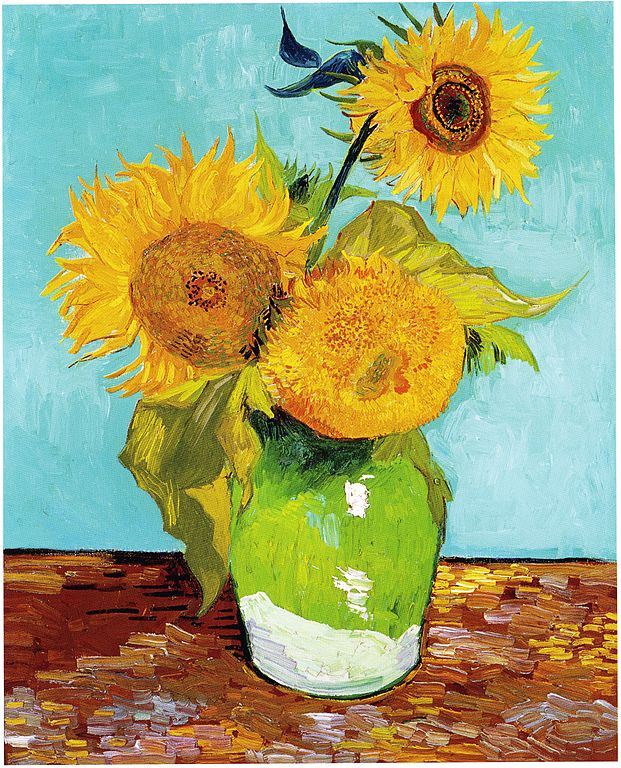

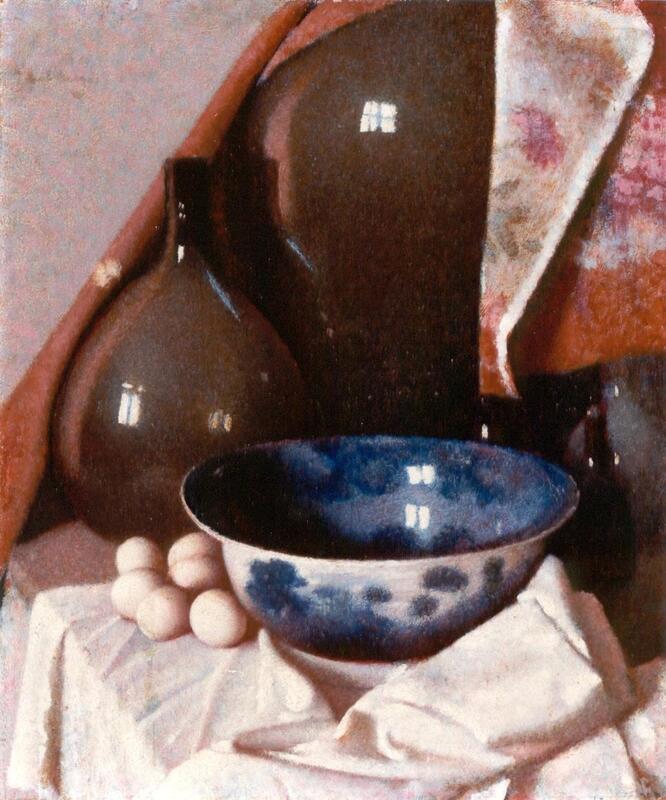

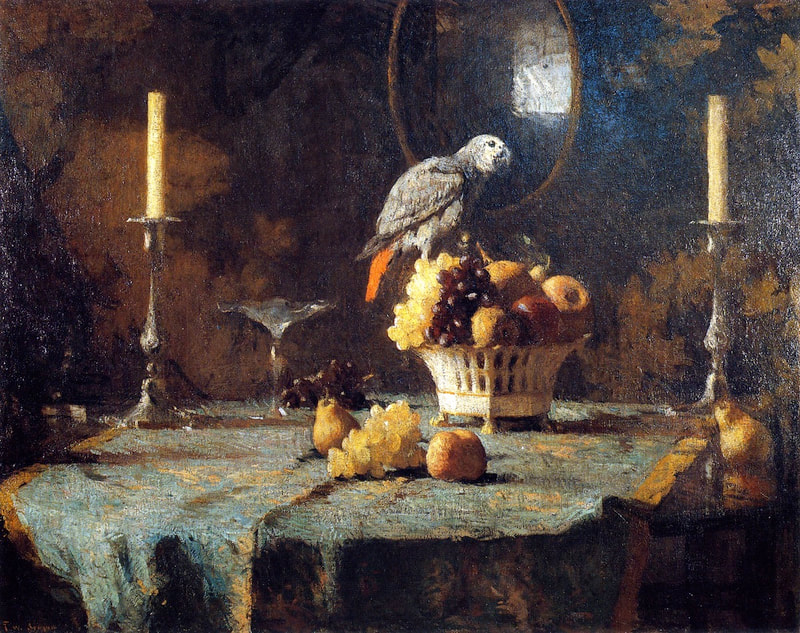

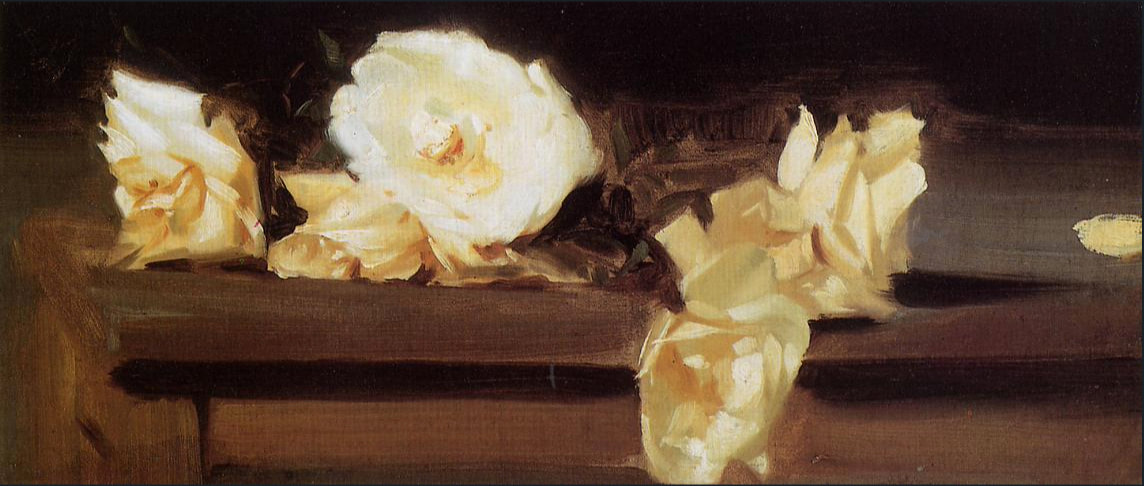

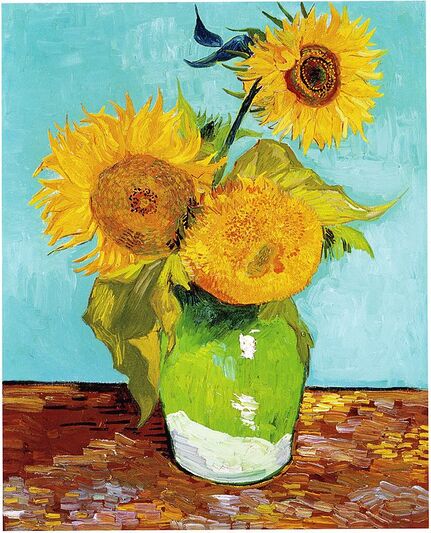

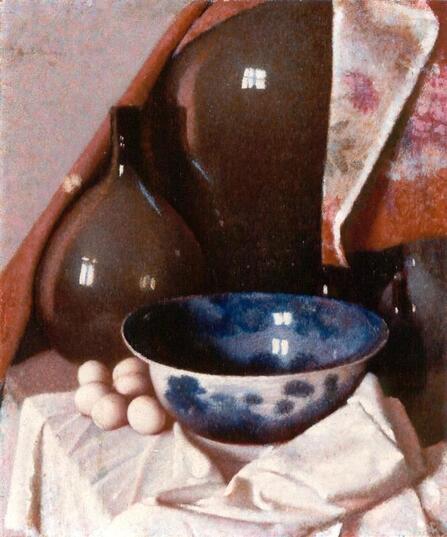

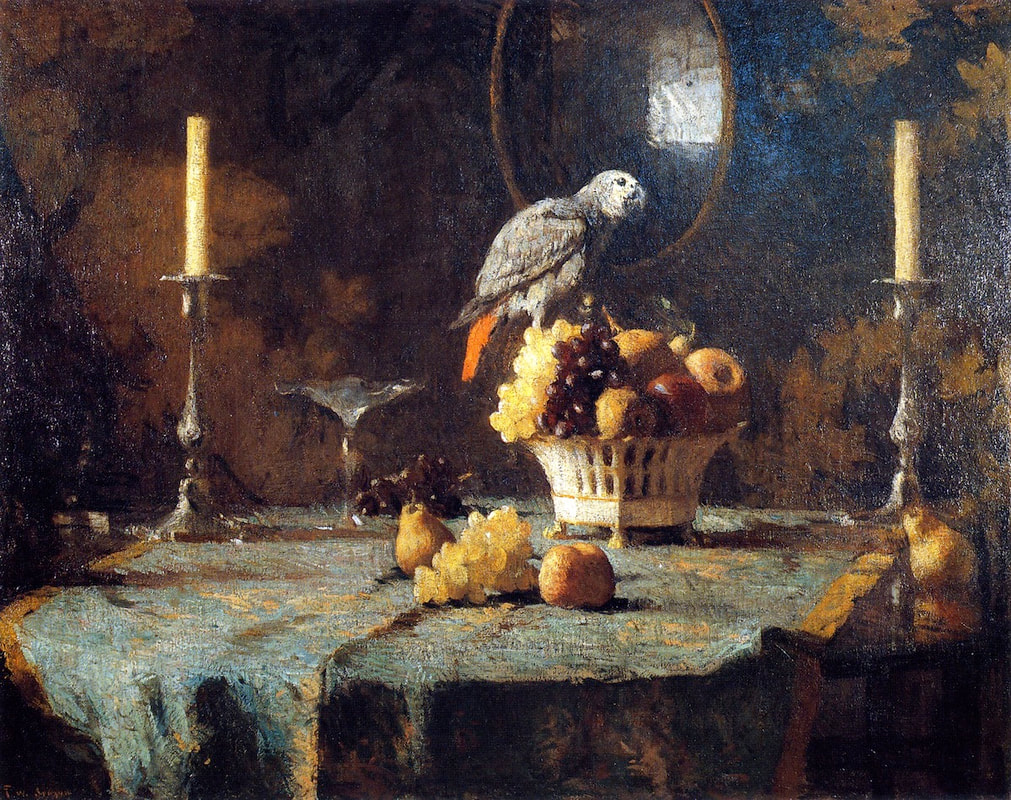

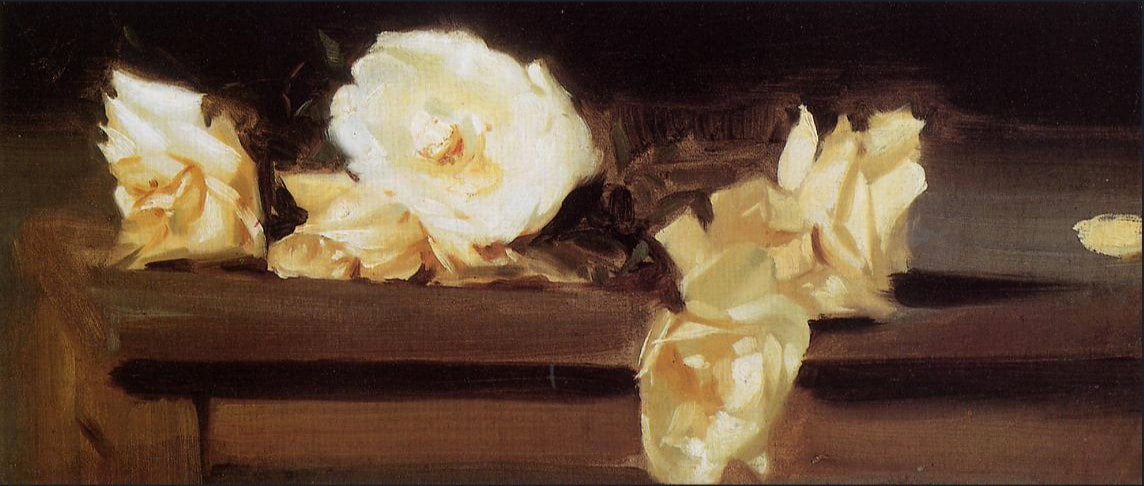

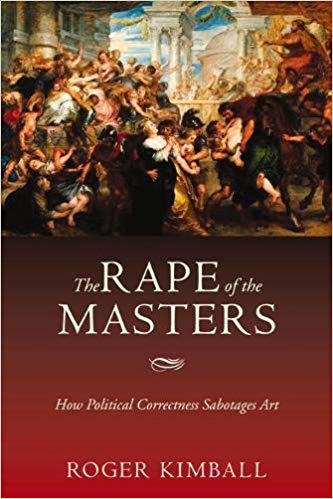

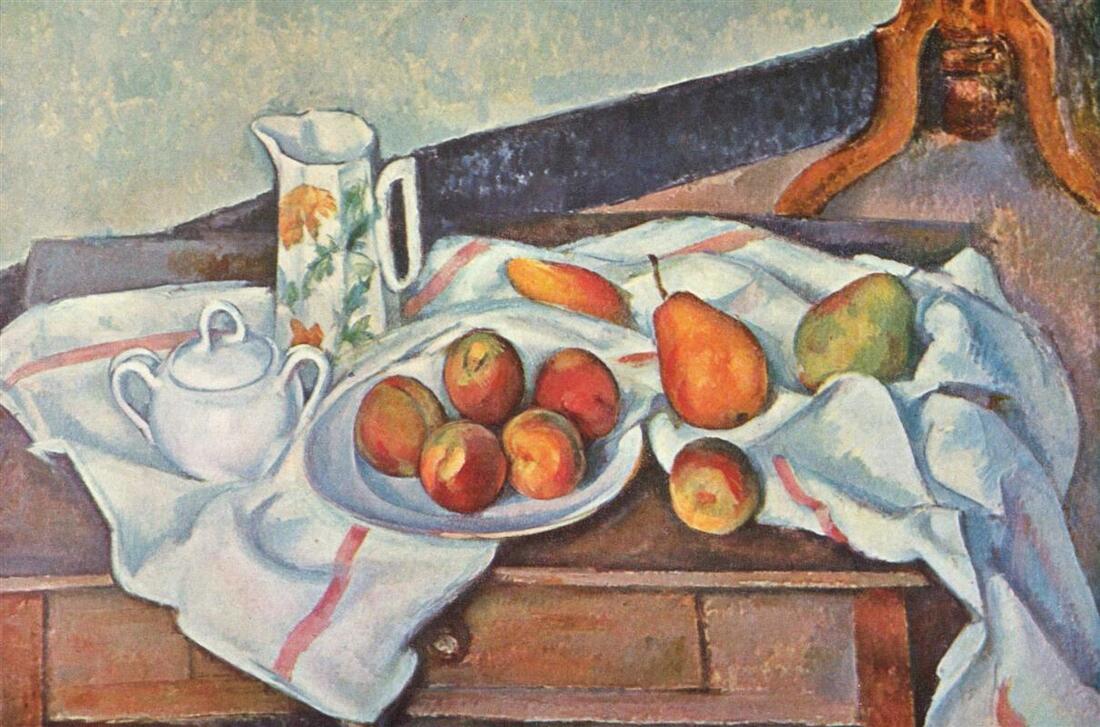

Still Life Pop Quiz! How many of the following ten famous (and not so famous) paintings do you recognize? How many were you able to identify? Tell me in the comments! Let's go through one by one and talk about the merits and or problems in each. I'll break these paintings down for you and give you my score for each one out of 10 (you can tell me whether you agree or not). I hope the following analysis of these 10 paintings helps you to feel more confident in judging still life paintings that you encounter and more able to enjoy beautiful works of art! 1. Still Life with Sugar by Paul Cezanne Cezanne was, by most accounts, an earnest soul and an extremely hard worker, but he was not particularly talented at the craft of painting. This may have been a primary cause that lead him to seek directions with his painting other than intentional mimesis of reality. This work is typical of his rift with traditional (accurate) drawing techniques in favor of a jarring rupture with perspective that he claimed to make for compositional reasons. While having a pleasing sense of color and some fun forms and textures, the overall lack of visual unity here is a very serious defect; others, later in the 20th Century, used his work to justify even more serious and ugly departures from the beauty of truth. Because I know his inaccurate drawing was intentional, I am particularly offended by the work of Cezanne. On a scale of 1-10: 4.5 2. Basket of Fruit by CaravaggioThe early Baroque master Caravaggio's fidelity to light and form is wonderful. This basket glowing with golden light. The form of the subject has an accuracy that shocked audiences of his time and still remains potent for us today. His love of detail particularly is remarkable; his work has a visual unity beyond what the Dutch school painters achieved in painting similar subjects. A possible flaw to mention is the consistant, cut-out edge that surrounds almost every object. Later, more advanced small 'i' impressionist artists like Valazques and Vermeer would have blurred and softened such edges for the sake of depth and visual unity. On a scale of 1-10: 8.5 3. Still Life with Lemon by PicassoGarish colors, vertigo-causing swirls and lines, textures that seem best described as crude and even rude... Picasso takes the errors of Cezanne and makes them the center of his work which is an assault on the tradition of beauty in the visual arts -- and painting in particular. This destruction, enabled by a cabal of artists, art dealers, art critics, and big money, ravaged the practice of painting and caused great confusion in the general population as to the general sense of beauty in the 20th century. Hopeful signs of cultural recovery today are in spite of works like these. On a scale of 1-10: -10 4. Still Life with Sand and Shells by Robert Douglas HunterHunter: Beautiful, peaceful compositions. Always with a sense of calm and harmonious colors and object sizes, Hunter described his work as "little tunes." Informed by the Boston School tradition of painting, his technical work is usually strong, but can sometimes suffer from a look of shallowness of form and hard-edged-ness in shape. On a scale of 1-10: 7.5 5. Still Life: Vase with Three Sunflowers by Vincent Van GoghLovely color contrast and lively shapes. Van Gogh is a "post-impressionist" particularly noted for his thick paint application and his departure from strict realism. Though many claim his lack of realism was intentional, much evidence indicates that he recognized his inability to render the fullness of seen beauty as a shortcoming in his work. His letters seem to indicate his dissatisfaction with his own draftsmanship. A little-known fact is that he worked through the Bargue Drawing Course numerous times in an effort to improve his ability to accurately depict shapes and forms. I believe that, despite these shortcomings and due to his honesty in striving towards beauty - not making his deficits into virtues - his paintings, including this one, often have charm and beauty. On a scale of 1-10: 5 6. Still Life with Teapot by Emil CarlsenAn American painter from Denmark, Emil Carlson produced paintings with great balance and craft. He is particularly notable for his atmosphere, where all of the edges are beautifully balanced and the objects pop out and sink into their background just as they do in life. His paintings have magnificent technical strength and often involve beautifully brilliant colors, like those of his contemporary impressionists. On a scale of 1-10: 9.5 7. Still Life with Blue Bowl by Carl SchmittA really underrated American artist from the 20th Century, Carl Schmitt combines many of the experiments of the impressionist and post-impressionists in beautiful lively still life painting. Where Seurat's " A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" feels stifled and stiff, Schmitt is able to take the truths of optical color mixing and make subtle and amazing works with these rather non-traditional methods. If you are able to see these paintings in real life, their vibrant liveliness jumps off the canvas in a way totally unexpected and far greater than mere reproduction can accomplish. If his work has a flaw it is a bit of a lack of incisiveness in drawing, shape, and form -- more than made up for by his brilliant sense of depth and color. On a scale of 1-10: 9 8. The Dining Room Table by Frank BensonA loosely painted beautiful still life full of color and atmosphere. This is a typical example of a Boston School Still life, with lovely variety of edges and tones that produce depth and visual interest. A bit rougher than many still life paintings, but thoroughly entertaining in its uneven brush marks resolving into a beautiful sense of reality. On a scale of 1-10: 8.5 9. Still Life with Fruit, Wanli Porcelain, and Squirrel by Frans SnydersThis painting by Snyders is typical of the exacting detail and delicacy of good Flemish painters from his period. The great critique of their work is that while they have drawn every detail faithfully, they often miss a sense of the grand sweep of light, the sense of forms, and the overall atmosphere (I discussed this concept in my post on Breadth). A glaring example in this painting is the way that the plate on the table feels 'flat' - the front and back feel as if they are the same distance away from the viewer due to an evenness in treatment that robs it of its three dimensional sense of projection. While epic and rich in its subject matter, Boston School impressionists would rightly regard this as a primitive way of painting which Valazquez and Vermeer would later take great steps beyond. On a scale of 1-10: 6 10. Roses by John Singer SargentA seemingly effortless small sketch, this painting is a really impressive piece of visual poetry. The economy of means by which Sargent painted these flowers and arranged this pleasing little composition is so deft as to be almost taken for granted. Visual truth is presented well, if not completely, in its essentials leading the painters of the Boston School to refer with grudging admiration to Sargent as "the greatest of sketch artists." The magic and liveliness of Sargent's sketches so often surpass even the carefully completed work of the other greatest painters in history; it is a truly remarkable accomplishment. On a scale of 1-10: 9 I mention Vermeer and Velasquez a few times above. They are role models for Boston School painters, though a bit tricky to use in a study like this, as neither was known as a still life artist. Nonetheless, here are examples of the work of each for your reference: Bonus: The Milkmaid by Johannes VermeerBonus: The Waterseller of Seville by Diego VelasquezMaybe you agree with my analysis, maybe not - do tell. The important thing is that you remember that art can and should be judged, and that art should be beautiful. Roger Kimball's book The Rape of the Masters: How Political Correctness Sabotages Art was a fun, quick read from cover to cover. If you have ever been subjected to recent art criticism, this book provides catharsis. With humor and wit, Kimball confronts the obfuscating rhetoric that clothes political agendas -- not with his own competing rhetoric and agenda but by trying to let the artwork speak for itself. Whereas so-called art critics, bedecked as they are with prestige, institutional backing, and economic privilege, tend to flabbergast, intimidate, and discourage, Kimball encourages his readers to take a step back, have a good laugh at what currently passes for academic art insight, and counter it with a good dose of common sense. He often quotes artists themselves, as well as their contemporaries, to provide a clearer view of how they understood each artwork under discussion. Kimball considers a number of cases of art criticism that he assures us are representative of the current practices in the field (rather than outliers or exceptions), systematically exposing them and de-jargonizing them while diagnosing the intellectual diseases at work in each case. Having been through a number of college art history courses at a prestigious university, I can attest that his selection of texts certainly is representative of the fare foisted upon my classmates and I. One of my favorite instances here is a perfectly ridiculous text on "The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit," a beautiful group portrait by John Singer Sargent. The art historian who penned the text, one Professor Lubin, wanders so far afield that he starts reading perverse sexual meaning into words that don't even appear in the painting or in the title of the painting, but only in the pun on the title that the author admits to fabricating himself and that would have never occurred to the artist or the patron. It is in this bizarre way that he purports to "find" the meaning inherent in the artwork. From the book: "Professor Lubin's first point is that the French word for box, boîte, is only one letter and an accent mark away from the surname of the painting's subject: "Boit." "The Boit Children makes a visual-verbal pun by translating into Les Enfants de (la)Boît(e): the children of Boit and the children of the box." In fact, it is not the painting that makes the pun - and a silly enough pun it is - but Professor Lubin. And that's just the beginning of the charade.... "Professor Lubin readily admits that "It far oversteps the bounds of credibility to think that Sargent had any of this in mind before, during, or after he painted the painting." "For this relief, much thanks"! (Hamlet I:1) But then he cheerfully tells us that, notwithstanding what Sargent thought, we shouldn't be surprised "if somehow a psychic transfer or transmutation occurs between the verbal part of the creative mind... and the visual part." Psychic transfer? Transmutation? What is this, Shirley MacLaine meets art history?" Kimball quotes Lubin at length as the latter goes on (and on) about vagaries of the significant connections between certain - ahem - anatomical parts and the uppercase and lowercase of the letter 'e' (because -- don't forget! -- the letter 'e' is conspicuously absent from the name in the title of this painting! Following this?). All he has to do here to reveal Lubin's absurdity to the sound-minded is simply to quote him! In short, Kimball has done a wonderful service: He selects representative tests of art criticism, translates them for his reader in the context of the real work, the practices of the artist, and his times, and calls them out for what they are: self-serving academic and political garble dressed up in very fancy pseudo-psychology, pseudo-philosopy, and, most of all, just words, words, words... Words that ultimately obscure the paintings they purport to describe. Kimball continues on more witty and enlightening jaunts with paintings by Courbet, Rubens, Winslow Homer, and van Gough and their critical aggressors, valiantly defending the honor of the masters along the way. While he does a delightful job of pointing out the ridiculous aspects of the current state of art criticism and the intellectual rot that has for a long time posed as learning, I do dock Kimball a few points for trying to enlist to his aid a number of artists and critics who are complicit in this decay. For example, Kimball amusingly rips apart a piece of art criticism or two dealing with the canvases of Marc Rothko, but not before a few pages of dedicated to apparently serious appreciation of that painter. He seems to accept, if not validate, Rothko's place in the canon of Western Art as written by the very critics and academics he is lampooning. Rothko's current prestige and place in the art world relies almost solely on the basis of the ridiculous climate of the arts made possible by the decay of common sense and the love of beauty. The only way Rothko can be so highly revered as he currently stands is through the rejection of beauty and the acceptance in its place of fatuous theory and political jockeying.

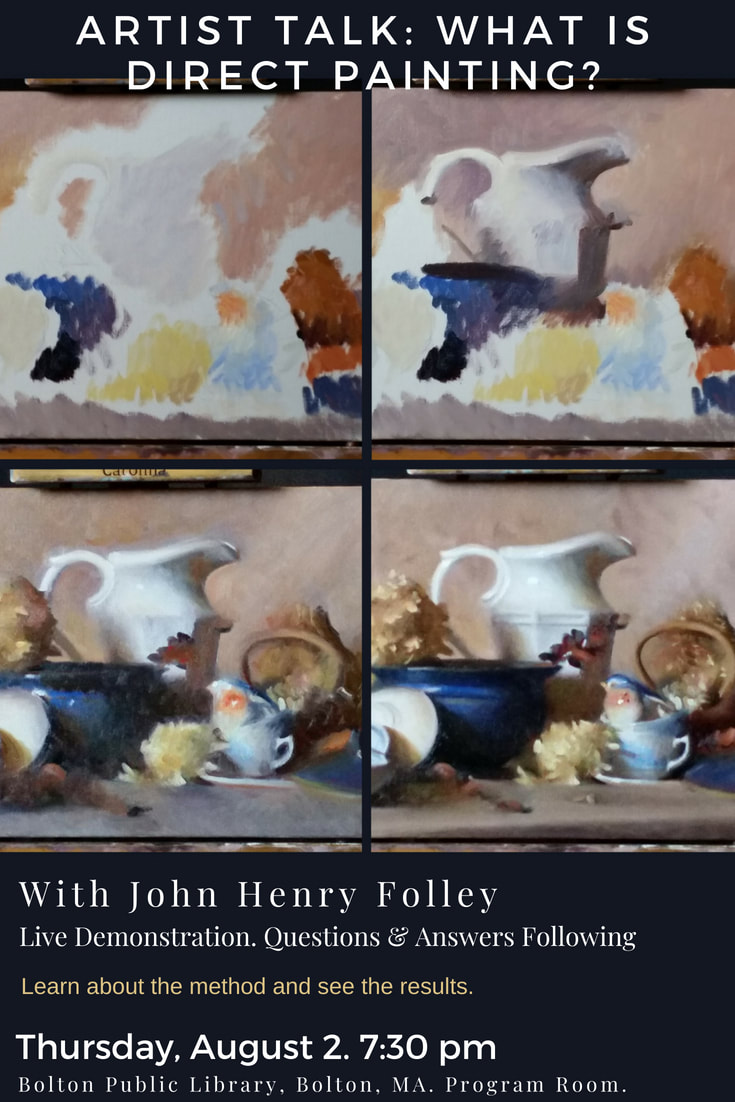

Kimball also tries to enlist Clement Greenberg as an ally in his interpretation of Paul Gauguin without putting Greenberg in his proper context as one of the primary founders of the strains of art history attempting to do away with beauty as a central theme in understanding art. In fact, Greenberg himself was one of the first critics to reject the beautiful representation of volumetric form in paintings as meritorious and in its stead have a theory of art that valued "flatness" per se. This of course flies in the face of the tradition of Western painting which, from the time of Leonardo and even before, considered the beautiful and accurate rendering of three dimensional form one of the key marks of beauty and indicators of the accomplishment of an artist. For readers interested in the subject of art history and those looking for further entertainment along these lines, I recommend Tom Wolf's The Painted Word to understand the earlier stages of the sickness of the art world and gain a broader critique of certain facts that Kimball either takes for granted or doesn't recognize as part of the problem. Overall The Rape of the Masters proves clarifying, fun, and refreshing. I would heartily recommend it to anyone, especially those who deal with art critics or interact with the art world establishment in any way. From the author himself: "... I hope that The Rape of the Masters will provide some inoculation against academic intimidation. The claims made by the critical marauders I discuss in this book are so outlandish, and they are typically expressed in language that is so rebarbative, that many people are stunned into acquiescence or at least into silence. It pleases me to think that The Rape of the Masters will help counteract that anesthesia, prompting more people to object to the objectionable." I think that Kimball's book will bear out these hopes admirably. Students in particular, approaching the discussion of art within mainstream academia or other art criticism circles, will do well to arm themselves with this work before undergoing the mental assault typical of the field. I wish I had been thus armed myself. What do you think? Does art criticism intimidate you? Do you have a hard time with interpretations of paintings that seem to be irrelevant to what's actually on the canvas? "I don't know anything about Art..." We hear it all the time and even use this excuse ourselves. Most of us don't make movies, or write novels, or cook haute-cuisine meals, yet we feel free to make such statements as, "that film is not worth watching," "his first novel was better than his second," or "this restaurant has delicious food." At the same time, we often feel inadequate to make the most basic judgments about one painting versus another, or whether a collection could be considered good or bad; beautiful or - we'd never dare say - ugly. So many of us accept that Art is a topic reserved for "them;" some group of people with access to a particular education or unique innate gifts. Or we think that Art is too subjective for anyone to be able to claim any expertise. "I know what I like" is as far as we can get. In reality, Art (as in, for example, the fine art of painting) is a pursuit with objective measurements and standards. One way to become a discerning art appreciator is to learn about technique. To start off, I'd like to share about Direct Painting, the technique in pursuit of which I left my comfortable Metro-Washington, D.C. job and brought my little family to New Hampshire in order to train in the atelier of Paul Ingbretson. After several years of focused study, I'm now producing my own art with this method and teaching it to my own students. It's the best way that I have encountered to get to the heart of a subject: its form, its depth... and especially its color. In an upcoming blog post, I'm going to tell more about what Direct Painting means and how it's distinguished from other approaches in oil. For now, I'd love to invite any locals who are interested in learning about Direct Painting - and adding this fascinating approach to their arsenal when it comes to art appreciation - to my upcoming talk and painting demonstration at the Bolton Public Library. This talk is taking place as part of my ongoing exhibit, Light and Form. The exhibit is on display until August 9. If you can't make it to the talk, I do hope you'll drop in another time to see the collection (all of the included paintings were executed using the Direct Painting Method) before the exhibit wraps up.

If you're not local and can't make it to the talk, please stay tuned here as I share more on this topic in the coming weeks! Update: Read What is Direct Painting, Part II here. Thank you to everyone who came out to my talk and demonstration! It was a great time! |

AuthorHello there, I'm John H. Folley, an oil painter in the Boston School tradition. Thanks for visiting the Beauty Advocacy Blog, where it's my job to help you become a more discerning art appreciator. Connect with John:

Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

|